You’re in the blocks. Your heart is pounding. The gun sounds. And then… everything you know about running goes out the window. here is 400m Running Strategy to win every 400m Race!

The 400 meters isn’t a sprint. It’s not a distance race either. It’s a brutal hybrid—a controlled explosion followed by a battle against your own body’s chemistry. Most runners lose the race in the first 100 meters by going too hard, or in the backstretch by going too slow. Very few actually have a strategy at all.

This is the real problem: people treat the 400m like it’s just a longer 200m, or a short 800m. It’s neither. The 400m has its own logic, its own pacing pattern, and its own mental demands. World-class runners—from Michael Johnson’s legendary 43.18 seconds to modern sprinters—all follow the same race structure. And science has now explained why.

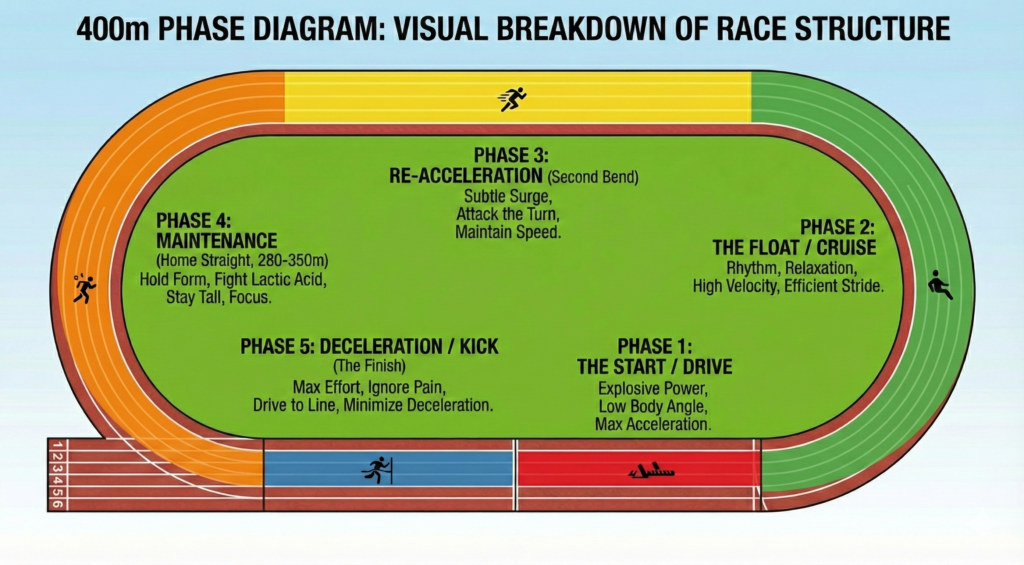

Whether you’re running 48 seconds or 52 seconds, the strategy is the same. You have four distinct phases, and if you execute them properly, you’ll run faster and hurt less. If you don’t, you’ll experience what coaches call “double jeopardy”—you’ll run slower AND it will hurt more.

Let’s break down exactly how to run the 400m.

The Science Behind 400m Pacing: Why Positive Splits Win

Here’s what surprises most runners: every 400m world record ever set was run with positive splits—meaning the first half was faster than the second half.

This isn’t because elite runners get tired. They get tired too. It’s because of how your body’s anaerobic system works. When you run at race pace, your muscles accumulate a metabolite (scientists call it “X-factor,” though the exact mechanism is still debated) that limits muscle function. The key insight: the earlier you generate this buildup, the more time your body has to clear it through the bloodstream. That’s why going out fast and gradually slowing is actually faster than trying to run even splits.

A University of Wisconsin physics study modeling world-record 400m races found that the optimal strategy is: maximum acceleration for the first 60-80 meters, followed by a continuous, gradual deceleration to the finish. The deceleration should reduce your velocity by about 20% from your peak speed, not 40% or 50%.

This is the fundamental principle: minimize how much speed you lose, and you’ll run faster.

Phase-by-Phase Breakdown: How to Execute the Perfect 400m

Phase 1: Acceleration (0–80 Meters) — “Go All Out”

This is the only phase where you run at true maximum effort.

As you explode from the blocks, accelerate hard through the curve. Your goal here is to catch competitors who are running in outside lanes, and to establish yourself as a force in this race. Get to near-maximum velocity as quickly as possible. You should be running hard, fast, and aggressive—this is 100% effort.

Coaching cue: Think about driving your hips forward and picking your knees up. The first 30 meters are about overcoming inertia; the next 50 meters are about reaching peak speed. Don’t worry about conserving energy yet. You don’t have a lot of alactic energy anyway—you’ve only got about 7-8 seconds of it.

By 80 meters, you should be approaching your maximum velocity. For reference, Michael Johnson’s split at 100m was 11.10 seconds, which means he ran the first 80m in roughly 8.8 seconds.

Phase 2: The Float (80–200 Meters) — “Find Your Rhythm at 97%”

This is where most runners fail. And it’s where the race is actually decided.

At 80 meters, you transition into what sprinters call the “float.” This is the fastest you can run while staying relaxed. Not slow, not easy—relaxed. Think of it as the edge of insanity, where you’re moving at 97% of your max effort, not 100%.

The critical technique here: reduce your arm range of motion (ROM), but maintain your leg cadence. This seems counterintuitive, but it works. Keep your legs turning over at the same frequency you established in the acceleration phase, but stop pumping your arms so aggressively. You don’t swing them as far back or forward. Why? Because your arms will become critically important later in the race, and you’re conserving arm energy now.

This phase typically lasts 50–100 meters depending on the runner. During this time, you should hit your 200m split. For a runner with a 22-second 200m PB (personal best), aim for a 23-second first 200m—just 1 second slower. For a runner with a 25-second 200m PB, aim for 26 seconds.

The key question most runners ask: “How do I know if I’m at 97% and not 95% or 99%?” You can’t, not precisely. But here’s the secret: run a few practice laps where you literally hit maximum speed, feel what that is, and then consciously back off just slightly. Do this in training, and you’ll develop the feel for it in racing.

This phase is “the most difficult part of the race” because it dictates your final time. Go too fast here and you’ll blow up around 320 meters. Go too slow and faster runners will pass you.

Phase 3: Mental Preparation & Gradual Re-acceleration (200–280 Meters) — “The Squeeze”

You hit the 200m mark. You feel okay, maybe even good. But something’s different—your legs are starting to feel the lactic acid buildup. This is the most psychological phase of the race.

Here’s what happens: you don’t suddenly accelerate. Instead, you gradually increase speed over the next 50–80 meters. Imagine you’re squeezing the accelerator slowly—not punching it, squeezing it. Increase your arm frequency and range of motion slightly, push a bit harder with your legs, but do it gradually as you go around the bend.

Mental cue: This is when you mentally prepare for the final push. You should be thinking about the big effort coming at 300 meters. You’re no longer in the “find your rhythm” phase—now you’re in the “prepare for hurt” phase. Expect the lactic acid. Expect the burning in your quads. Mentally rehearse how you’ll get through it.

By 280 meters (the beginning of the final straight), you’ve gradually increased your effort, and lactic acid is now truly accumulating. You should NOT try to do a sudden speed change here. That wastes energy. The squeeze takes the whole bend.

Phase 4: The Drive Phase (280–350 Meters) — “Form and Aggression”

Coming off the final turn onto the homestretch, you have 120 meters to go. This is where form becomes absolutely critical, because your legs are now firing on borrowed time. Your nervous system is tired. Lactic acid is burning. Oxygen is limited.

This is exactly when most runners’ form falls apart—they shuffle, their arms drop, they fold at the waist. Elite runners do the opposite. They exaggerate their form.

Form cues for the final turn:

- Drive your knees higher. Even though your legs feel dead, consciously push your knees up. This keeps your hips forward and prevents the shuffle that slow runners have.

- Pick up your arms. Start pumping harder, with emphasis on the upward drive, not the forward swing. Create “lift” in your torso, not exaggerated, sloppy windmill arms.

- Stay tall. Lean from your ankles, not your hips. Don’t fold forward.

- Increase arm frequency and ROM. By 280m, your arms are back in the game, and they become your legs’ life support.

This is also where you can make up positions. If someone got ahead of you during the float, the 280-350m zone is where you hunt them down. Your form is better, you’re driving harder, and if they haven’t trained properly for this segment, they’re breaking down.

Phase 5: The Final Push (350–400 Meters) — “Survive”

You have 50 meters. If you’ve paced properly, you don’t have much speed left to give, but you still have something. This is pure mental toughness.

By this point, there’s not much conscious thought happening. All the practice of your form cues and race strategy should be automatic. Your body is in survival mode. Your legs are screaming. Oxygen is maxed out. You’re asking your muscles to do something they don’t want to do.

What matters now:

- Focus on one thing. Pick one form cue—usually arm drive or posture—and laser-focus on that single thing. Your brain can’t handle multiple instructions when it’s this fatigued.

- Pain is information, not a stop sign. The burning you feel is lactic acid, not injury. Keep going.

- Lean slightly into the finish. Many runners unconsciously slow down in the last 10 meters. Don’t. Run through the finish line.

If you’ve executed the first four phases properly, you might surprise yourself with how much speed you still have left at the end. If you went out too hard in the backstretch, you’ll be struggling.

Pacing by the Numbers: Your Target Splits

Here’s the practical version: base your pacing on your 200-meter personal best.

If your 200m PB is 22 seconds:

- First 200m target: 23 seconds (1 second slower)

- Second 200m target: 25 seconds (3 seconds slower)

- Total: 48 seconds

If your 200m PB is 24 seconds:

- First 200m target: 25 seconds

- Second 200m target: 27 seconds

- Total: 52 seconds

If your 200m PB is 26 seconds:

- First 200m target: 27 seconds

- Second 200m target: 29 seconds

- Total: 56 seconds

These splits follow the “positive split” pattern and are based on research showing optimal energy distribution.

Alternative approach: Add 4 seconds to your 200m PB, and that’s a conservative target 400m time. So if you run a 24-second 200m, aim for 48 seconds in the 400m.

Training for the 400m: Build Speed, Speed Endurance, and Mental Toughness

Having a great race strategy means nothing if you haven’t trained for it. The 400m requires three training components that work together:

Component 1: Speed (Maximum Velocity Development)

You can’t run a speed you haven’t trained. If your top speed is only 8.5 m/s, you can’t suddenly run at 9.0 m/s in a race.

Sample speed workouts:

- 3–4 sets of 3 × 30m accelerations @ 95-100% effort with full recovery (3’/6′ rest)

- Flying 30s: 30m acceleration + 30m fly zone @ 95-100% (maintaining top speed)

- 3 × 3 block starts or sled pulls @ 95-100%

These should be done early in the week when you’re fresh. Total volume: around 500m per week.

Component 2: Speed Endurance (Maintaining Speed While Fatigued)

This is where you train the ability to hold near-maximum velocity when lactic acid is accumulating.

Sample workouts:

- 3–6 × 120–150m @ 95-100% effort with 6–10 minutes recovery

- 80–100–120–100–80m @ 95-100% with 6–8 minutes recovery

- 100–200–300–200–100m pyramid @ 80-89% effort

Total volume: around 500m per week.

Component 3: Special Endurance (Lactic Tolerance)

This is the most brutal training—you’re teaching your body to function when lactic acid is sky-high.

Sample workouts:

- SE-1: 150–300–150m @ 95-100% with 12–15 minutes recovery

- SE-2: 2–4 × 300m @ 90-100% with 15–30 minutes recovery (this one needs LOTS of rest)

- SE-2: 300–400–300m or 300–600–300m @ 90-100%

- Lactic tolerance: 2 × 10 × 100m @ 70-80% effort (2000m total)

- Alternative: 4–7 × 45-second hard efforts @ 80-85% with 3–5 minutes recovery

Total volume: around 1000m per week.

Important note: These aren’t casual runs. Special endurance training is where you build mental toughness and lactic acid tolerance. This is the training that makes the final 100m of a race feel bearable.

Weekly Training Structure: Balancing Hard Work and Recovery

| Day | Workout | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | Speed (3–4 × 3 × 30m @ 95-100%) | Build maximum velocity |

| Tuesday | Tempo/Aerobic (2000–3000m @ 70% effort) | Base building, recovery |

| Wednesday | Speed Endurance (3–6 × 120–150m) | Hold speed while fatigued |

| Thursday | Tempo (2000–3000m @ 70%) | Active recovery |

| Friday | Speed (3 × Fly 30s or block starts) | Maintain top-end speed |

| Saturday | Special Endurance (300m repeats or 45-sec efforts) | Lactic tolerance, mental toughness |

| Sunday | REST | Recovery |

As you get closer to competition season (spring), shift to heavier special endurance work and reduce pure speed work. Your body adapts, and you want to be race-ready, not just fast.

Race-Day Execution: Putting It All Together

You’ve trained for weeks. Now it’s race day. Here’s your mental checklist:

Before the race:

- Visualize each phase of your race

- Remind yourself: “First 80m all out. Float at 97%. Squeeze at 200. Drive at 280. Survive at 350.”

- Create a pre-race routine (warm-up jog, strides, breathing) that you’ve practiced multiple times

In the blocks:

- Think about the start. You’ve drilled this a thousand times.

- Take a breath. Settle in.

0–80m:

- Accelerate hard. Catch competitors. Get to max speed.

- This should feel like you’re leaving it all out there.

80–200m:

- Shift mindset: relax and find rhythm.

- Reduce arm ROM, maintain leg cadence.

- Feel the pace, feel your competitors, but don’t get psyched out.

200–280m:

- Squeeze the accelerator slowly.

- Mentally prepare for the pain coming.

- Think about the final push.

280–350m:

- Drive knees, pick up arms.

- Exaggerate form.

- Push hard but under control.

350–400m:

- Focus on one thing (arms, posture, breathing).

- Let the practice take over.

- Run through the finish line.

Common Mistakes (And How to Avoid Them)

Mistake 1: Going out too fast in the first 200m.

Elite runners hit a first 200m that’s only 1–2 seconds slower than their 200m PB. Most age-group runners go 3–4 seconds slower. If you’re going way slower, you’re not taking advantage of your speed reserve.

Mistake 2: Floating too slowly.

The float should be 97% effort, not 85%. Many runners back off too much here and then can’t close the gap.

Mistake 3: Running an even split.

Yes, you learned about even pacing in the 5K. Forget that. The 400m is different. Positive splits are optimal.

Mistake 4: Losing form in the final 100m.

This is where the race is won or lost. If your form breaks down, you slow down 2–3 seconds. Exaggerate your form instead.

Mistake 5: Not practicing race strategy in training.

You can’t improvise strategy on race day. You have to practice hitting your splits in hard workouts first. Test different pacing approaches. Feel what works for you.

Your Next Steps

- Establish your 200m PB. If you don’t have a recent one, run a time trial.

- Calculate your target 400m time. Use the formula: 200m time + 4 seconds = conservative 400m goal. Or use the split-based approach above.

- Start with the basic training structure. Pick 3 days per week for hard training (one speed, one speed endurance, one special endurance), and fill the other days with easier paced runs and strength work.

- Practice your race strategy in workouts. Don’t just “do the workout”—execute your race plan. Hit your target splits. Feel the pacing. When it gets hard at 80% through, practice your form cues.

- Run a time trial or lead-in race. Get on the track at race pace and practice your four phases. See what feels right. Adjust.

- Mental preparation matters as much as physical training. The 400m is 50% mental. Visualize, practice positive self-talk, and develop a pre-race routine.

The 400m isn’t easy. But if you understand the four phases, execute your pacing strategy, and train the right energy systems, you’ll run faster and hurt less. That’s the promise of strategy.

Now get to the track.